As part of our highly successful ongoing outreach to Eastern European students, graduates and professionals, we sponsored a virtual presentation by Dr Claire White (MRCVS), of long-time partner, the internationally respected University of Bristol vet school, at the popular Junior vet Congress, 17th October 2020.

TRANSCRIPT

Good afternoon. My name is Claire White and I work for the University of Bristol and in this session, we are going to be talking about the role of the veterinarian in One Health.

As an introduction, I am going to discuss the principles of One Health, why veterinarians are important in One Health, what roles you might occupy if you are interested in One Health and how you can influence One Health principles, then consider what a world without veterinarians might be like inside the One Health concept.

You will all have read my biography, hopefully, and you will know that I am working at the University of Bristol and that my primary responsibilities are teaching veterinary students about public health and also running the university slaughterhouse, as well as conducting industry training and licencing of slaughtermen.

In previous roles, I worked for a red meat processor, responsible for supermarket supply, and before that, I was a farm animal vet. So, I have quite a wide range of experience, working with cows, sheep and pigs, from farm all the way to food, public health issues as well. I am also extremely interested in food sustainability and security across the world.

The concept of One Health itself has been around for a number of years, but it’s only really in the last decade we have actually looked at this concept with the name One Health. The One Health Taskforce, which is based in America, a group of veterinarians working for different bodies that are interested in working together on One Health, describes One Health as “The collaborative efforts of multiple disciplines working locally, national and globally, to attain optimal health for people, animals and our environment.”

So, this is the first mention of which One Health covers everything in the world in relation to the health of it, including the people and including animals. So, it’s the relationship between humans, animals and the environment that describes One Health.

Human and animal interdependency

The OIE, which is the world organisation for animal health, describes One Health as human and animal health being interdependent and bound to the health of the ecosystems in which they exist. So, you can’t have a healthy ecosystem without healthy humans and animals and vice versa. It’s sort of the holy trinity: they have to work together.

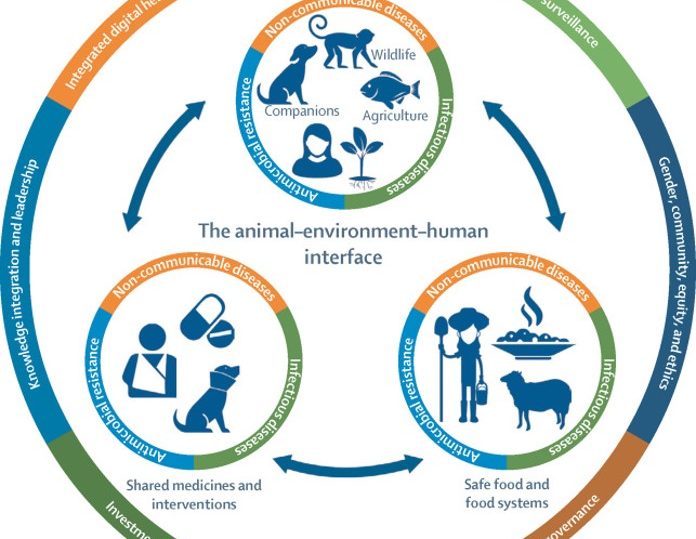

And you can see that in this diagram (3 min into video), that shows the shared environment, the safe food and ecosystems and shared medicines and interventions all relate to the animal/ human environment interface. And then we have these overarching principles that go around the outside, in relations to policy and legislation, gender, community, health systems, as well as integrated digital health and information, investment, care and financing. All of these things have to work together to achieve One Health.

And when we look in more detail at One Health and knowing that it means that it’s all animal/human interactions, and their relationship to the environment, the first stop is zoonoses and that’s at the front of everybody’s minds because of Covid. And it’s true, zoonosis is a big part of One Health but there is so much more to that and how it relates to the rest of animal/human interactions than just how can animals make you sick? How can you become sick from the environment?

Trade farming, agriculture and zoonotic diseases

Things like animal trade can have a big impact on One Health, bot only because it can spread diseases around the world, but because it can cause food security and sustainability issues, too. And we need to consider things such as farming systems – are they farming systems that are good for the environment? Are they farming systems that are bad for the environment?

Both types exist across the world and what many organisations are striving to achieve are better systems, better integrated farming systems, which, particularly in low economic and developing countries, actually improve things like gender equality.

So, integrated farming systems, where manure from the animals fertilises the crops and the waste from the crops then feeds the animals, are more productive systems. In these there is actually better gender quality. Better gender equality leads to better education for girls and when they mature into women, they tend to have fewer children and better career prospects.

So, you can see that One Health isn’t just about ‘Are you sick?’ It’s about how is the life of yourself and the animals you interact with and the environment better? And you can make changes in all of those areas just by very small or quite isolated changes in one aspect.

I’ve mentioned farming systems and food sustainability and food security; the ability of people to have enough nutritious food – not just enough food – and know that it can be produced in a way that doesn’t harm the environment is absolutely essential to One Health, because without nutritious food, people do not become healthy, do not become productive.

And sustainable agriculture is absolutely important because if we affect the environment to a serious extent, the rest of the ecosystem collapses as well.

So, it’s not just about what we can become sick from; it’s not just how we can make our food supplies better; we can also think about One Health as how we interact with our companion animals. And not just about can we be sick from our pets but how do they have health benefits for us? Walking a dog is good for your physical and mental health; having a pet, even if not one you walk, is good for mental health. So, there are many positive One Health benefits just to companionship with animals.

And then, lastly, and perhaps the one that gets considered least, is the involvement of biomedical research in One Health. So, in order for us to have better health, we have to conduct biomedical research. These involve animals or animal products to trial new therapies or treatments, or to understand diseases like cancer better. They involve animals, so the animals are involved in that interaction with humans. It’s not direct but they are still part of One Health because of their involvement.

And many of the things I’ve discussed here are encompassed in this diagram on the right-hand side, representing the UN sustainable development goals to be achieved by 2030. This is probably one of the best depictions of One Health, because it addresses 17 different areas the UN believes are important for improving human health, but also the health of the environment and the animals we interact with.

It has some fairly obvious points like zero hunger, no poverty, good health and wellbeing, but perhaps we hadn’t thought of gender equality being really important for One Health – and also responsible consumption and production and peace and justice and strong institutions. So, we have to consider all these goals together – work at them independently but realise they are related. I’ve already mentioned that improving food security and sustainability improves gender equality and improves education and improves health and wellbeing; all of those things that we may not necessarily think are related just to a particular farming system.

At the moment, we have a situation, which we all realise is the case because of Covid, but even without Covid, it’s important to remember that 75% of all emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic, so they have an animal or bird or insect origin. That shouldn’t really be surprising because, of course, it’s likely that diseases don’t just originate in humans; they’re going to come from the millions of different wildlife species that we have, or domestic species.

It shouldn’t be considered a threat, but it is something to bear in mind when we think about One Health, because as our world changes and as our interactions with animals change, it means there are new opportunities for these emerging infectious diseases to occur and Covid is a prime example of this. It also shouldn’t surprise you that 60% of infectious diseases have animal origins, too – or can be transmitted from animals to humans or the other way; it’s bidirectional. It shouldn’t be a surprise, but it is something to consider, because the moment you have wildlife or domesticated animals as part of the disease cycle, it becomes more difficult to control.

And, as I mentioned earlier, now our interactions with animals are changing, we need to realise how the way in which the way we interact with the world affects our likelihood of getting a zoonotic disease. Things such as deforestation and changed land use, expose us to new pathogens as we move closer to wild animals and society encroaches, we are going to encounter new pathogens and they are potentially going to spread to humans.

Intensified agriculture and livestock production drive the selection of new pathogens because of the opportunity for new pathogens to develop and spread between large numbers of livestock very quickly.

Illegal and poorly regulated trade of wildlife is another example of how a disease can spread across the world. The whole principles of phytosanitary agreements that I’ll mention later on, these health checks and requirements that need to be completed for animals moving between countries, exist to prevent the spread of diseases and to ensure that the global One Health situation is protected

We need not to forget that climate change encourages the spread of zoonoses or the emergence of zoonoses where they hadn’t been previously, because as the world warms, vectors and other conditions that promote the survival and proliferation of diseases spreads across the world. The warmer the world is, the more likely that more insects will survive winters and transmit vector-borne diseases

And last but not least, the issue that is at the front of everybody’s mind, before Covid, probably, is antimicrobial resistance. As we increasingly use antimicrobials, it drives the selection of resistant pathogens. That is inevitable. Every time you use an antibiotic, some of the bacteria do not get killed and that drives selection and increases the number of resistant bacteria species around.

And although there have been many improvements in antibiotic usage and responsible usage, particularly in Europe and the UK, there are still parts of the world where there is some improvement to be made. And because of the global nature of humans and of trade at the moment, it’s very easy for antimicrobial resistance to spread across the world.

So, if we know that these five factors here, amongst many others, are issues, then we know where we need to start to control them – and they are all intrinsically linked to those sustainable development goals I mentioned earlier on.

So, if we can improve responsible drug use, if we can reduce illegal trade of animals, if we can slow climate change, we can work towards sustainable development goals and try to improve the situation where we have less zoonoses emergence. And these considerations have been recognised by the World Health Organisation, the Food and Agriculture Organisation and the World Animal Health Organisation, so the tripartite guide to addressing zoonotic diseases in countries was written by these three organisations, recognising that food, agriculture, animals and human health are all linked.

So, it’s a One Health approach to controlling zoonoses. But remember this is only one part of One Health: everybody focuses on zoonoses and Covid pushes it front of mind, but it’s so much more than that, as I’ve already mentioned. And us, as veterinarians, probably reach into more areas of One Health than any other profession, because we’re involved in surveillance, we’re involved in trade, but we’re also involved in teaching and communicating information to students, to clients, we’re also involved in protecting humans and animals but also ensuring that diverse food production and economic growth is sustained.

The importance of veterinarians in One Health

We have so many different abilities and so much knowledge and so much reach that we encompass One Health every day. You’d actually have to try quite hard to be a veterinarian and not be involved in One Health. How much you recognise your involvement is different.

Why are veterinarians so important to One Health? Well, as I’ve mentioned, we have the skills and knowledge to be involved in all areas; we also have a holistic view of the interactions of animals with humans and the environment. We understand that humans become ill from animals, but also that humans benefit from interactions with animals and we understand that through the concept of Veterinary Public Health. The title in its own right explains that we understand that veterinarians and public health are linked – that we can improve public health through being a veterinarian.

And that can be something as simple as reducing antimicrobial usage to reduce microbial resistance or slow it down, but it can be also encouraging clients to vaccinate or worm their animals or to become involved in more projects on social interactions between humans and animals.

So, we can be directly involved in the management and research that drives systems forward, like myself, I was involved in the meat industry, so I was managing One Health from a food safety perspective and an animal welfare perspective for quite some time. And you can also be involved in the research, whether it’s biomedical research or research that improves our understanding of One Health.

But even if you are outside those roles, you are still involved in One Health as a veterinarian, because you are making contributions to wider society. And these contributions include things such as negotiating, drafting and upholding laws and international standards – World Health Organisation, EU, UK domestic legislation all have input and oversight from veterinarians – and these underpin One Health, because most of those laws are written to protect animal health, then also protect human health, too,

We can also be involved in global food security and consumer protection, whether making sure that meats in a country are safe to eat or not, or through the work of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (the FAO) and the World Health Organisation take a real interest in food security. And either through the work you do in practice, or for other organisations, that will contribute to the goals of the FAO or the World Health organisation.

So, you can also be involved in cutting edge science or discovery or teaching, academia, your own research to promote understanding of One Health. Things are changing all the time: research has recently found that the Guinea Worm, a worm in Africa that, in the ‘80s, infected over three million people, now reduced to 20 or 30 people, after finding that it has an animal reservoir. Knowing now that it has an animal reservoir, we understand better how to fully eradicate the disease.

Those cutting-edge pieces of science have happened with the contributions of veterinarians who understand One Health, who understand human health and how animals can be involved in it.

We can also be involved in protecting public health and animal health by controlling diseases and protecting animal welfare. That, perhaps, is the most obvious contribution that veterinarians make, but we’re protecting welfare and the human interaction with those animals because it’s not just about can we be sick, can we suffer because of interactions with animals – what about thinking can animals suffer because of interactions with us?

So, in our daily roles in practice and other roles, we will be protecting public health, animal health and animal welfare. We can protect society from fraudulent activities be it fraudulent sales of meat products, of animal products, or of animals themselves – or pets. And the World Trade Organisation, which is responsible for 98% of world trade has agreements, called sanitary agreements, which have animal health and One Health requirements written into them and they form the basis for trade between countries.

And those have received veterinarian input – and anyone who is involved in exporting animals or products is upholding those One Health principles. So, as a veterinarian, you can facilitate economic growth through small and large businesses, whether it’s making a farm business more efficient or more compliant and you can support that through sustainable farm or food production and trade, so without world trade and safe food goods, economic growth is impossible.

The FAO and the veterinarians who work in it, are responsible for preserving diverse methods of food production that are suitable for the environment. So, it would be bad for the environment, potentially, if intensive food production methods moved to certain countries of the world. So, these organisations and the veterinarians who work with them, protect diverse food production and still make it safe, meaning that those methods can still occur but with less of an impact on humans and the environment.

And lastly, one of the main contributions that veterinarians make is communicating these important messages to interested parties. We are really good at communicating really complex topics to people who do not have a scientific understanding or presenting it in the correct way to relevant people, such as government or other interested stakeholders. That’s a really important skill that veterinarians have – that we should recognise more often.

So now I have explained the contributions of veterinarians to one health, I want to show you some roles that can influence One Health.

There are many roles that focus on it within the civil service or state veterinary medicine, either in the UK or elsewhere, such as an Official Veterinarian role. In the UK, this ensures meat quality and meat safety and food safety as well and they exist within the Food Standards Agency and through their contractor, Eville & Jones, who you will be aware of.

Or you can be responsible for border inspection through the Animal and Plant Health Agency – and these veterinarians inspect imports and exports of animal and plant products and animals and plants themselves, as they enter or leave the country to make sure they are safe.

You can be a Government Vet, which is a general term for veterinarians who work within the government. And they can work for the Animal and Plant Health Agency, controlling infectious diseases or work for Defra, which has links with farming and the environment. Veterinarians there work on ensuring that farming methods don’t compromise the environment and promote welfare.

You can also work for the Health Agency in the UK, trying to protect humans and animals in their interactions and promote human health through their interactions with animals.

And lastly, Parliamentary Intern is a relatively new area of civil service. We have in the UK a veterinarian who is a member of the House of Lords, which is the most senior level of parliament, and the veterinarian who is the intern of this particular member of the House of Lords is involved in the Veterinary Policy and Research Foundation and is having a really in-depth grounding at really high levels of government decision.

Either work for the government or you can work for a non-governmental organisation – an NGO. We often think about these as charities and other organisations that work towards charitable aims. There are a few here that are involved in food and food sustainability, such as Send A Cow and Farm Africa. They work outside the UK but there are charities that work inside the UK that do the same thing.

Their successes so far have led to families that previously had no money for education to send their children to university in the UK, through the money they have been able to make through improved, sustainable and often organic farming practices.

So, they absolutely require a veterinarian input because they have to train people how to look after their livestock well and how to integrate it into their farming systems, which is a huge amount of work for a One Health veterinarian.

Alternatives include industry, such as pharmaceuticals, but think also food supply chain, which was my role, looking at animal health and welfare right through to the packet of meat on the supermarket shelf. But in pharmaceutical companies, I have colleagues that are veterinarian advisors who teach and train the veterinarians and advise veterinarians in practice on how best to use their drugs. They also engage directly with the farmers to ensure they are using those drugs and vaccines properly.

And the one area I want to remind everyone where you have as much influence over so many animals as anywhere else is in clinical roles. One Health reaches into clinical roles, such as pet and companion, but also farm and equine: engaging with a client about vaccinating or worming their pet or even the safety aspects of feeding them raw meat to pets.

Research and teaching passes on One Health knowledge to veterinarians or students and academia can lead you down the path of discovering new One Health concepts.

The last area is animals in research. Every single one in the UK has a responsible veterinarian, who manages their health and welfare, so any mouse involved in a cancer trial has a veterinarian looking after them. This ensures the reliability of the trials, which will hopefully provide sound new knowledge for human health, with treatments for cancer and many other diseases.

How do we access roles in One Health?

Most veterinarians are already involved in One Health by dint of their clinical practice work, but if you want to move into One Health-focused roles, not necessarily clinically based, we can look elsewhere.

Luck and contacts at university help. Ask your career lecturers, first. They have gone down the same path and will know people who are in One Health roles. They will know where to look, might be able to encourage you into further study, summer schools or internships. They exist in the UK, as I’ve already mentioned, for example access to summer schools here for a small number of European veterinarian students.

There are also internships for recent graduates in Europe, in Switzerland, in animal health organisations across there, so it’s worth looking and talking to your university lecturers about where those opportunities might exist.

You can also contact professional bodies, whether it’s national or international, because they will also be aware of opportunities. So, the Federation of Veterinarians of Europe, the FVE, are a really good organisation, as well as the European College of Veterinary Public Health. These will both know of either internship or further study opportunities and will also be able to encourage you to look at potential job roles, either in the UK or elsewhere.

Once you know where opportunities might lie, then you have to make a start, in clinical practice, as an OV or working in industry – all great places to start, because you learn a lot of the formative knowledge you need; food safety, communication, understanding of pharmaceuticals or the meat industry – and then you can move into different roles.

You need patience and the route might to One Health roles might not be the ones you think. They’re so broad and diverse and you never know what might come up or what will interest you. So, make a start, talk to people, see what happens.

This video of colleagues in UC Davis, America tells you how to present yourself for a One Health role and how skills you have developed studying for a veterinarian qualification actually give you skills that you can take away into other roles – not every role you occupy has to be a veterinarian one.

Veterinary skills are as diverse as just about anyone will ever have and you can apply those to any situation involving One Health that doesn’t require a veterinarian qualification. Stress your skills in, say communicating, or analysing, or presenting, or reactive to challenging situations in order to get a role that demands them.

For people interested in One Health, there is literally a whole world of job opportunities. It covers every animal, the environment, human – and I know veterinarians that work in human medicine, but explaining the principles of One Health from the veterinarian perspective. I know people who work for the environment who do the same.

And working in practice you can bring all that back to the individual client and explain all of those things to them in a clinical role. So, you can have a global ear on One Health and communicate that clients that might not understand it or have access to that information in any other way.

What would a world without veterinarians look like?

Without veterinarians, people and animals would suffer increasingly from famine, disease and death; there would be higher levels of environmental pollution; economic growth would stagnate, with no sustainable agri-food production and trade; and we would move to a lack of food diversity plus cultural damage due to the loss of traditional farming and food production as intensive farming methods might well reduce animal welfare and environmental care – intensive farming doesn’t inevitably do this, but would be more likely without vets.

So, veterinarians make the world go round – it’s not just money that makes the world go round!

Remember that you are making a difference with One Health, even if the public don’t realise this; the public and the consumer have a right to complacency. In the same way that they assume their car has been manufactured safely they assume there are people in the background making their food and environment safe.

Thank you for listening to today’s presentation. I hope you have enjoyed it and will enjoy the rest of the conference.

Thank you.